When Seattle’s population exploded at the turn of the 20th century, in the wake of the Klondike Gold Rush, subdivisions were platted, and streets were built at a furious clip.

When Seattle’s population exploded at the turn of the 20th century, in the wake of the Klondike Gold Rush, subdivisions were platted, and streets were built at a furious clip.

As the resident count swelled from 43,000 in 1890 to 237,000 in 1910, city leaders realized that they needed to build a parks system in the city, or Seattle wouldn’t have one at all.

So they turned to The Olmsted Brothers, America’s most prestigious landscape architecture firm from Brookline, Mass. who also had a hand in developing other cities’ park systems, as well as national parks.

The resulting work, which occurred on and off from 1903 to 1936, would forever shape Seattle’s landscape.

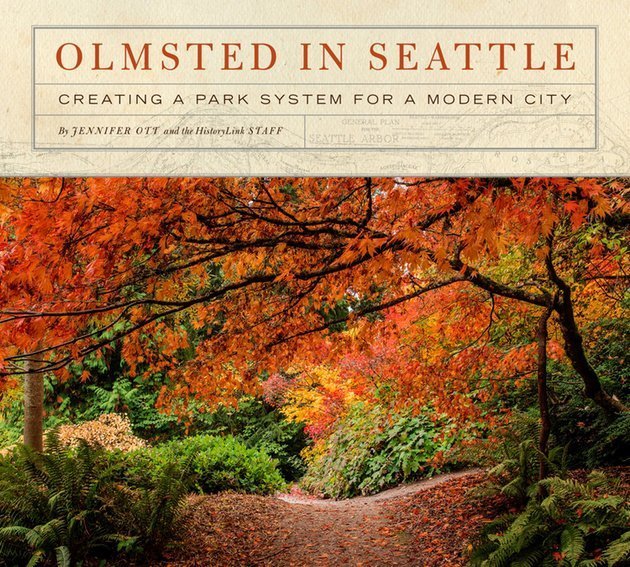

Environmental historian and author Jennifer Ott detailed this profound transformation in her latest book, “Olmsted in Seattle: Creating a Park System for a Modern City,” which launches next month with an event at the Central Library.

Today, 82 Seattle parks are directly connected with the Olmsteds, whether they were completely designed by the brothers or benefited from the advice they gave to Seattle city planners.

“If you live in Seattle, you are touched by the Olmsted parks plan today,” Ott told The Seattle Public Library Foundation. “We have this incredibly diverse and effective park system because of the work that was done 100 years ago.”

These parks include Alki Beach, Cal Anderson, Volunteer, Discovery, Golden Gardens, and Gas Works parks, as well as several scenic parkways. The last Olmsted park developed was the Washington Park Arboretum.

Ott says the development of Seattle’s extensive and iconic parks system took immense galvanization of political will – something she didn’t fully appreciate until researching for this book.

And it’s something not to be taken for granted today.

“The things we love about these parks need to be invested in,” Ott says, adding they need constant maintenance. “There are so many challenges because they can be loved to death.”

When pressed to name her favorite Olmsted park, Ott instead names a chain of parks linked by scenic parkways: South Seattle’s Jefferson Park, Cheasty Boulevard, Mount Baker Boulevard and Park, and Lake Washington Boulevard Park.

It “captures Olmsted’s vision,” she says, creating accessible scenic corridors that allow people to experience views of the city, Puget Sound, Olympic Mountains, the forested hillside, the bungalow neighborhood, and access to the lake – all in one string of landscapes that one can find “only in Seattle.”

“Olmsted made it possible so that someone like me could have views,” Ott says. “I wouldn’t get to experience those amazing things about Seattle had they not been reserved.”

The launch event for “Olmsted in Seattle” takes place 2 to 3:30 p.m. Saturday, Nov. 16 at the Central Library. Proceeds from books sales benefit Friends of Seattle’s Olmsted Parks. Place a hold on the book before it hits Library shelves here.